The Graz Psychological Laboratory

from the beginnings in 1894 to 1945

Alexius Meinong: The founding of the Graz Psychological Laboratory

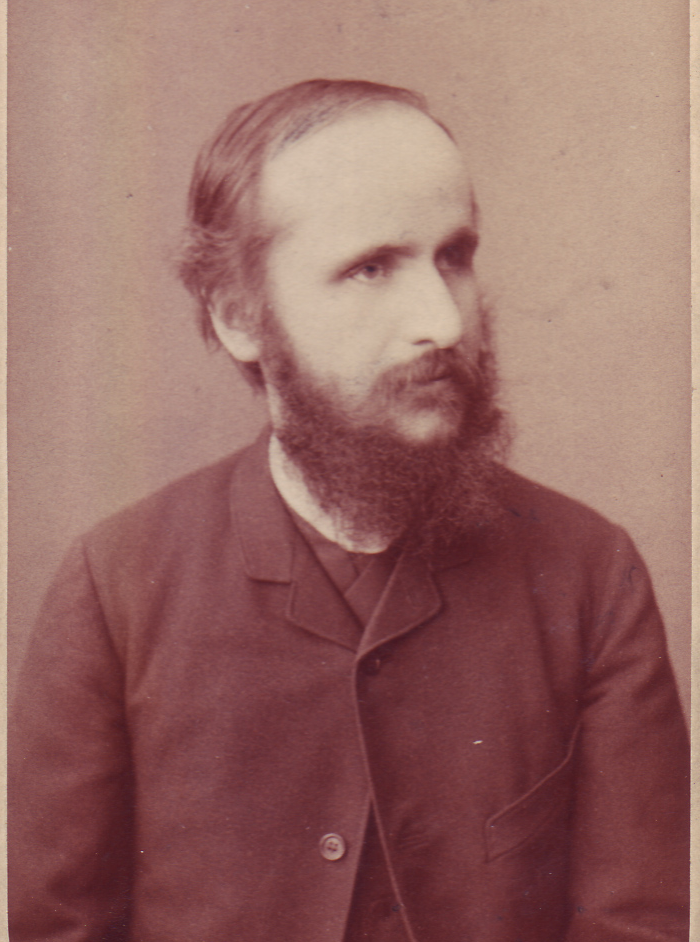

The institutional anchoring of psychology at the Karl-Franzens University of Graz is thanks to Alexius Meinong, Ritter von Handschuchsheim. Born in Lemberg in 1853, he received his doctorate in the summer of 1874 with history and philosophy as his main subjects at the University of Vienna. At the suggestion of Franz Brentano (1838-1917), he habilitated at the Faculty of Philosophy in Vienna in 1878 with his "Hume Studies I. On the History and Critique of Modern Nominalism". When Alois Riehl (1844-1924) accepted an appointment at the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg in 1882 to succeed Wilhelm Windelband (1848-1915), Meinong was appointed to the chair of Extraordinarius of Philosophy from Vienna to Graz, which had become vacant after Riehl; he was appointed full professor in spring 1889.

Meinong had already begun to hold the first experimental psychology exercises in the winter semester of 1886/87, after he had already offered the first college with demonstration experiments in Vienna in 1880 (Meinong, 1921, p. 105). The production of the equipment required for the exercises was financed from his own funds. In 1893, further equipment was donated by Anton Oelzelt-Newin (1854-1925) (Meinong, 1978, p. 95). Like Christian von Ehrenfels (1859-1932) and Alois Höfler (1853-1922), Oelzelt-Newin (1854-1925) was one of Meinong's students who had already known him from his four years as a lecturer in Vienna and came to Graz with him. Thanks to his persistent efforts, Meinong was able to receive the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Culture and Education to grant him an endowment of 400 guilders to set up an "experimental-psychological apparatus". In January 1895, this institution was authorized to bear the name "Psychological Laboratory". In 1895, the laboratory, which was housed on the second floor of the university's main building, had around 200 pieces of equipment. Over the following years, the equipment was expanded to include instruments from companies such as Diehl (Leipzig), Spindler & Hoyer (Göttingen) and Zimmermann (Leipzig).

The Graz Psychological Laboratory was the first of its kind in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. With his "object theory", Meinong went on to provide the conceptual framework for experimentally oriented Gestalt psychological research in Graz (see Meinong, 1904a). The distinction between "grounding objects" ("inferiora") and "grounded objects" or "objects of a higher order" ("superiora") formed the theoretical basis on which the Graz school of Gestalt psychology was based. In his posthumously published "Selbstdarstellung", Meinong (1921) described Christian von Ehrenfels' (1890) treatise "On Gestalt Qualities" as the "most important preliminary work" for the theory of object-foundation. In an article entitled "Über Vorstellungsproduktion", which appeared in the anniversary volume "Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie" published by Meinong (1904b) on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory, Ameseder (1904) attempted a psychological interpretation of the concept of foundation. Meinong (1904c, p. VIII) also saw "the psychological side of foundation" in this treatise. Ameseder argued as follows: In order for the superius notion of the difference between the two colors to be formed from the inferiority notions of red and blue, an as yet unknown psychological factor must be assumed. He called this factor "production" and contrasted the non-produced elementary conceptions of red and blue with the superius conception of the difference between the two colors as a "produced conception". "Production" therefore means "the coming into being of certain ideas" (Ameseder, 1904, p. 488). We can therefore say that the difference between the elementary ideas of red and blue is captured through production.

Stephan Witasek and Vittorio Benussi: The protagonists of the Graz Psychological Laboratory

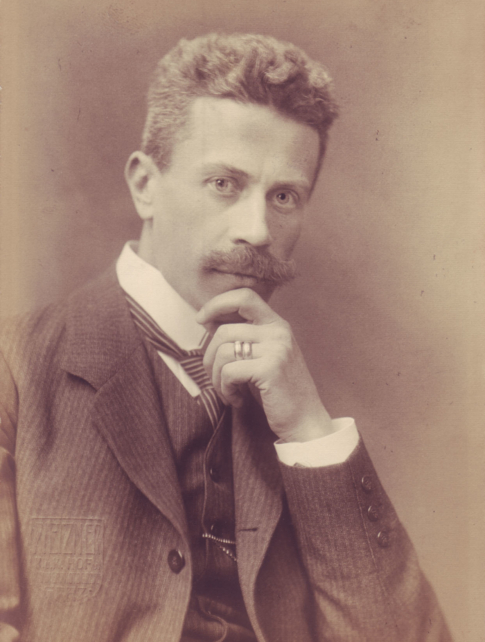

A few years after setting up the laboratory, Meinong retired from experimental psychology in order to devote himself entirely to his philosophical studies. A progressive eye condition may have been another reason for this decision. Stephan Witasek (1870 - 1915) initially took over the management of experimental psychology research. He was one of the first employees at the Graz Psychological Laboratory. He was awarded his doctorate in 1895 with a dissertation on "Investigations into Complexion Theory" - with philosophy as his major subject and mathematics and physics as minors. In 1899, he habilitated with a thesis entitled "On the nature of geometrical-optical illusions". After Witasek was appointed ad personam as a salaried associate professor of "Philosophy with special consideration of experimental psychology" in 1913, he was also officially appointed head of the Psychological Laboratory in 1914. Witasek had a wide range of interests. His publishing activities (1895-1901) began with general psychological issues, some of which we would today classify as cognitive and emotional psychology. With his work "Zur Analyse der ästhetischen Einfühlung" (1901), he began to deal with problems of art psychology. In 1904, his highly acclaimed monograph "Grundzüge der allgemeinen Ästhetik" was published, which was also translated into Italian in 1913. Later, with the monographs "Grundlinien der Psychologie" (1908) and "Psychologie der Raumwahrnehmung des Auges" (1910), general psychological topics again came to the forefront of his interests. Unfortunately, Witasek died just one year after his appointment in 1915 at the age of only 45.

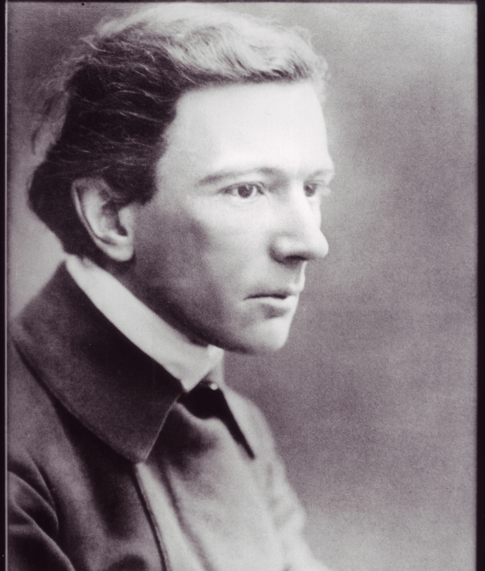

After Witasek's early death, the laboratory work was continued by Vittorio Benussi (1878-1927). Through him, experimental psychological research in Graz received significant impetus. While Witasek's strength lay more in the field of systematics (see his excellent textbook "Grundlinien der Psychologie"), Benussi was an ingenious experimenter. With his imaginative experimental designs, he brought international recognition to the Graz Psychological Laboratory. His publications were reviewed in all major European and American journals. The renowned American psychology historian Edwin G. Boring (1957) came to the conclusion in his work "A History of Experimental Psychology": "Benussi was an able experimenter, in fact, the most productive and effective experimental psychologist that Austria had had" (p. 446).

Born in Trieste, Benussi enrolled at the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Graz in the winter semester of 1896/97. He completed his studies in 1901 with a dissertation entitled "Ueber die Zöllnersche Figur". An expanded version of this work was published in 1902 in the renowned Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane under the title "Ueber den Einfluss der Farbe auf die Größe der ZÖLLNER'schen Täuschung". In 1905, he habilitated with a thesis entitled "Zur Psychologie des Gestalterfassens (Die Müller-Lyersche Figur)", which had already been published a year earlier in the anthology "Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie" edited by Meinong (1904b) on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory. In an extremely remarkable stroboscopic experiment, he succeeded in inducing stroboscopic and non-stroboscopic illusory movements (Benussi, 1912). As stimulus material he chose the Müllersche-Lyersche and Zöllnersche figure patterns familiar to him from earlier experiments, which were broken down into "phase images". Benussi saw the proof of non-stroboscopic illusory movements as a decisive indication of the central position of the concept of gestalt as a mediating process ("production") for the creation of geometric-optical illusions. However, this view did not go unchallenged, and the problem of illusory movement in particular sparked a fierce debate with representatives of the Berlin School of Gestalt psychology, especially Kurt Koffka and his colleague Friedrich Kenkel (1913), who saw no evidence for the existence of a mediating psychic process in the non-stroboscopic illusory movement described by Benussi.

However, Benussi was not only concerned with issues of perceptual psychology. His creative period in Graz also saw the publication of his monograph "Psychologie der Zeitauffassung" (1913), in which he examined the relationship between "subjective" and "objective" time in great detail. Using Schumann's "time sense apparatus" in conjunction with a "sonic hammer" or a "spring pendulum device" constructed by him, he was able to demonstrate time distances in a precision range of milliseconds in comparative experiments.

Benussi also dealt with issues that today would be classified under the heading of "psychophysiology". In a study on "The Respiratory Symptoms of Lying" (1914), he explored the question: "Do we breathe differently when we are sincere and differently when we are not?" (S. 514). Benussi assumed that the "finer, more constant manifestations of expression" consisted neither in the frequency nor in the depth of breathing, but "in the distribution of innervation over the individual respiratory phases". He therefore calculated the relationship between inspiration and expiration time and compared the inspiration/expiration quotients (I/E quotients) of the pre- and post-phases of a "lie test" with those of the pre- and post-phases of a "sincerity test". The test subjects sat in a reclining chair. A "Marey's pneumograph" was attached around the chest, which was connected to a "Marey's air capsule" with a tube. Respiratory activity was recorded on a 2.10 m long sooted paper strip, which was set in motion by a "Kymographion" with a second marker. The results of the experiment, which became known in the specialist literature as the "quotient laws", state that if test subjects tell an untruth (as instructed), the I/E quotient should be lower in the pre-phase of a statement than in the post-phase; if, on the other hand, they answer truthfully, the I/E quotient is expected to be higher in the pre-phase of a statement than in the post-phase.

The First World War and the end of Meinong's school of psychology

The years following Witasek's death proved to be extremely difficult for Benussi. Fritz Heider (1896-1988), Meinong's last doctoral student and founder of balance theory, described him as "a marginal man who stood between two cultures" (1970, p. 134). He was undoubtedly burdened by the scientific dispute with the representatives of the Berlin School of Gestalt psychology. Insurmountable difficulties also arose during the years of the First World War, above all due to his Italian nationality. Although the appointment committee ranked Benussi primo loco for the position of Professor of Philosophy and Head of the Psychological Laboratory, the proposal was not forwarded to the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Culture. Ministry of Culture in order "not to jeopardize the national integrity of the University of Graz" (cited in Antonelli, 1994, p. 25). Without an academic perspective commensurate with his qualifications, Benussi had no alternative but to leave Graz. He returned to his native city of Trieste in November 1918. In October 1922, Benussi was appointed full professor at the University of Padua without a competitive tendering process due to his outstanding reputation ("per chiara fama"). Tragically, he took his own life on November 24, 1927 at the age of 49.

After Benussi's departure from Graz, Meinong was once again at the beginning of his efforts to systematize experimental psychology. It had not been possible to fill the hard-won position that had become vacant after Witasek with Benussi. As it turned out, no one else from the circle of postdoctoral lecturers at the time, such as Ernst Mally (1879-1944), Othmar Sterzinger (1879-1944) or Otto Tumlirz (1890-1957), was in a position to continue the tradition of the internationally renowned Graz Psychological Laboratory. Meinong's death on November 27, 1920 - Wilhelm Wundt also died in August of the same year - marked the end of the "Graz School of Psychology" (see Höflechner, 1997; Mittenecker & Seybold, 1994). In 1919, Meinong was able to fill the position of demonstrator with Ernst Mally, who had returned from the war. Mally, a former student of Meinong's, had already habilitated in philosophy in 1913. He took over the provisional management of the laboratory in 1922. In August 1923, he was appointed Extraordinarius ad personam and on August 10, 1925, he succeeded Meinong as full professor. However, this was a professorship for philosophy, which did not include any teaching obligations for experimental psychology (cf. Höflechner, 1997, p. 82).

After Benussi, Othmar Sterzinger continued the research work in the Psychological Laboratory on a part-time basis. Sterzinger, who obtained his doctorate in Giessen in 1912, habilitated in experimental psychology with Meinong in 1920. In 1928 he was awarded the title of associate professor, and in 1940 he was appointed associate professor (cf. Höflechner, 1997, p. 83). However, his empirical contributions were limited to attention psychology studies (Sterzinger, 1924, 1927) and animal studies on the chemical influence on the sense of time (Sterzinger, 1935); later his main interest was in art psychology (1938/39).

On November 13, 1944, Ferdinand Weinhandl (1896 - 1973) was appointed to the professorship that had been vacant after Mally. He received his doctorate from the Faculty of Philosophy at the University of Graz in February 1919. Although Meinong had succeeded in obtaining a position for him as a demonstrator at the Psychological Laboratory, Weinhandl left Graz in the fall of 1919 to initially work as a publishing editor in Munich. In September 1922, he habilitated in philosophy under Heinrich Scholz at the University of Kiel with a thesis entitled "Zum Problem der Urteilsrichtigkeit" (On the problem of correctness of judgment). Although Weinhandl had studied under Meinong and Benussi, the method of "Gestalt analysis" (1927), which he founded, did not represent a further development of the concepts and methods of experimental Gestalt psychology in the sense of Witasek and Benussi. This also applies to the "Gestalt Lecture Test" (GLT) developed by Weinhandl (1960), which sees itself as a Gestalt-analytical interpretation of character.

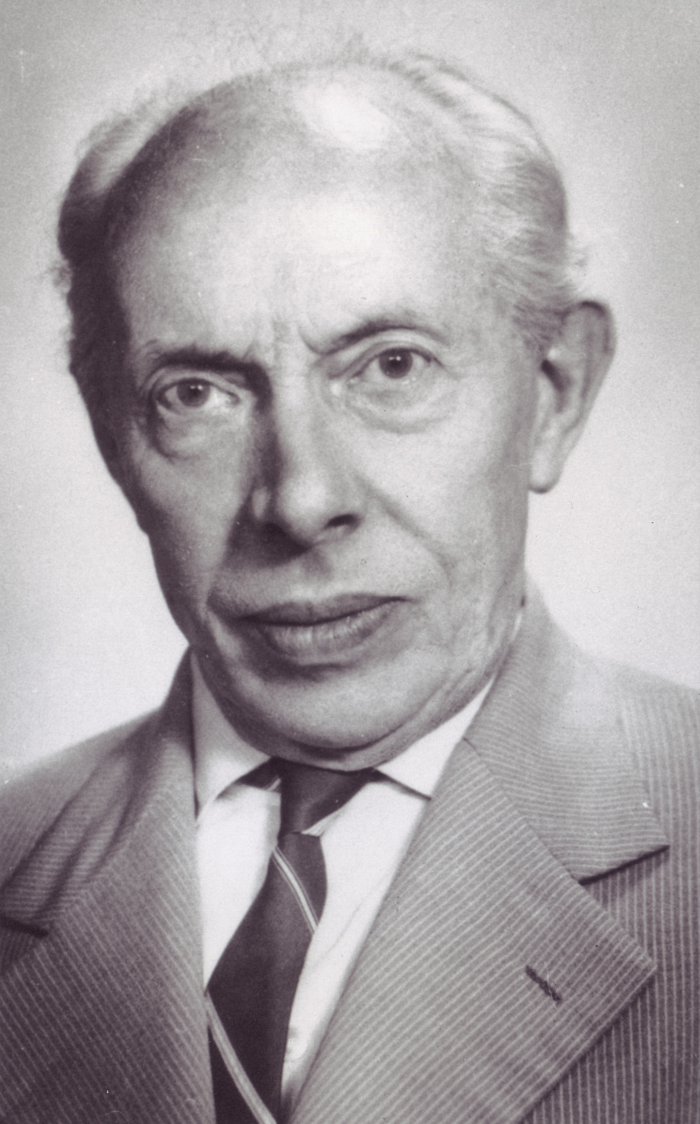

Meinong's last doctoral student was Fritz Heider (1896 - 1988). He completed his studies in Graz with a dissertation entitled "On the subjectivity of sensory qualities". Soon after completing his studies, he sought contact with prominent representatives of the Berlin School of Gestalt Psychology (see Heider, 1970, p.136) - with a letter of recommendation from Benussi. He attended lectures by Wolfgang Köhler (1887 - 1967) and Max Wertheimer (1880 - 1943); he became friends with Kurt Lewin (1890 - 1947). Lewin, who was appointed director of the "Research Center for Group Dynamics" at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) in 1947, founded the psychological field theory, a dynamic model for the analysis of individual and social behavior that attempted to combine basic concepts of Gestalt theory with physical concepts such as "field" and "force". In 1927, Heider went to Hamburg to take up an assistant position with William Stern (1871-1938). Two years later, he accepted an invitation from Kurt Koffka to Northampton (USA), where he worked in his laboratory at Smith College and in the Psychological Research Department of the Clark School for the Deaf. Political developments in Germany prompted him to remain in the United States, contrary to his original intention. In 1947, he became a member of the graduate faculty at the University of Kansas. From 1963 until his death, he was a Distinguished Professor in the Psychology Department at the University of Kansas. With his groundbreaking work in the field of attribution and balance theory (see, among others, his monograph "The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations", published in 1958), Heider became a pioneer of modern social psychology. Huber (2007, 2012) provides an introduction to the methods, concepts and research topics as well as a detailed account of the institute's history, on which this overview is also based. It was not possible to go into the history of the institute after 1945. Here it is sufficient to refer to the volume "100 Years of Psychology at the University of Graz" published by Mittenecker and Schulter (1994). A special volume of the journal "Psychologische Beiträge" also attempts to provide an overview of the research activities of the Institute of Psychology around 2000 (Huber, 2002). In 1900, the Psychological Laboratory moved to the building at Universitätsplatz 2. Some of the historical equipment of the former Psychological Laboratory can be seen in a permanent exhibition in the corridor on the 3rd floor. Some of this equipment has been briefly presented elsewhere in a virtual tour.

Author: Helmuth P. Huber

The portrait photos were kindly provided by the Alexius Meinong Institute of the University of Graz.

-

Albert, D., Mittenecker, E., & Nährer, W. (Eds). (1994). 100 Jahre Psychologie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. Katalog zur Ausstellung [100 Years Psychology at the Karl-Franzens-University of Graz]. Graz, Austria: Universitätsverlag Graz.

-

Ameseder, R. (1904). On the production of imagination. In A. Meinong (Ed.), Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie. On the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Graz (pp. 481-508).

-

Antonelli, M. (1994). The experimental analysis of consciousness in Vittorio Benussi. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

-

Benussi, V. (1901). On the Zöllner figure. Unpublished dissertation. University of Graz.

-

Benussi, V. (1902). On the influence of color on the size of Zöllner's illusion. Journal of Psychology and Physiology of the Sensory Organs, 29, pp. 264-433.

-

Benussi, V. (1904). On the psychology of Gestalt perception (The Müller-Lyer figure). In A. Meinong (ed.), Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie. On the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Graz (pp. 303-448). Leipzig: Barth.

-

Benussi, V. (1912). Stroboscopic illusory movements and geometric-optical gestalt illusions. Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie, 24, 31-62.

-

Benussi, V. (1913). Psychology of the conception of time. Heidelberg: Winter.

-

Benussi, V. (1914). The respiratory symptoms of lying. Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie, 31, 513-542.

-

Boring, E. G. (1957). A history of experimental psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

-

Ehrenfels, C. v. (1890/1960). On "Gestalt qualities". In F. Weinhandl (ed.), Gestalthaftes Sehen. Results and tasks of morphology (pp. 11-43). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

-

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

-

Heider, F. (1970). Gestalt theory: Early history and reminiscences. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 6, 131-139.

-

Höflechner, W. (1997). On the development of experimental psychology at Austrian universities until 1938. In D. Albert & H. Gundlach (Eds.), Apparative Psychologie: Geschichtliche Entwicklung und gegenwärtige Bedeutung (pp. 67-86. Lengerich: Pabst.

-

Huber, H. P. (Ed.). (2002). Psychological contributions (Vol. 44, No. 4). Lengerich: Pabst.

-

Huber, H. P. (2007). The Graz School of Psychology around Meinong. In K. Acham ed.), Natural science, medicine and technology from Graz (pp. 375-396). Vienna: Böhler.

-

Huber, H. P. (2012). The Graz "Psychological Laboratory" around 1900. Methods, concepts, research topics. Psychologische Rundschau, 63 (4), 218-227.

-

Koffka, K. & Kenkel, F. (1913). Contributions to the psychology of gestalt and movement experiences. I. Studies on the relationship between appearance variables in some so-called optical illusions. Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane, 67, 353-449.

-

Meinong, A. (1904a). On object theory. In A. Meinong (ed.), Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie. On the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Graz (pp. 1-50). Leipzig: Barth

-

Meinong, A. (ed.). (1904b). Studies on object theory and psychology. On the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Graz. Leipzig: Barth.

-

Meinong, A. (1904c). Preface. In A. Meinong (ed.), Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie. On the tenth anniversary of the Psychological Laboratory of the University of Graz (pp. V-X). Leipzig: Barth

-

Meinong, A. (1921). Alexius Meinong. In R. Schmidt (Ed.), Die deutsche Philosophie der Gegenwart in Selbstdarstellungen (pp. 91-150). 2nd ed. 1923 (pp. 101-160). Leipzig: Meiner.

-

Meinong, A. (1978). Self-representations. Vermischte Schriften (edited by R. Haller). Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt.

-

Mittenecker, E. & Schulter, G. (Eds.). (1994). 100 years of psychology at the University of Graz. Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt.

-

Mittenecker, E. & Seybold, I. (1994). The development of psychology at the Karl-Franzens-University of Graz. In E. Mittenecker & G. Schulter (Eds.), 100 years of psychology at the University of Graz (pp. 1-41). Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt.

-

Sterzinger, O. (1924). On the testing and investigation of abstract attention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 23, 121-161.

-

Sterzinger, O. (1927). On the so-called distribution of attention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 29, 177-196.

-

Sterzinger, O. (1935). Chemopsychological studies on the sense of time. Journal of Psychology, 134, 100-131.

-

Sterzinger, O. (1938/1939). Grundlinien der Kunstpsychologie (2 vols.). Graz: Leykam.

-

Weinhandl, F. (1927). Gestalt analysis. Erfurt: Stenger.

-

Weinhandl, F. (1960). The Gestalt reading test, its interpretation and evaluation. In F. Weinhandl (Ed.), Gestalt vision. Results and tasks of morphology (pp. 365-383). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgemeinschaft.

-

Witasek, S. (1895). Studies on the Complexion Theory. Unpublished dissertation, University of Graz.

-

Witasek, S. (1899). On the nature of geometrical-optical illusions. Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane, 19, 81-174.

-

Witasek, S. (1901). On the psychological analysis of aesthetic empathy. Zeitschrift für Psychologie und Physiologie der Sinnesorgane, 25, 1-49.

-

Witasek, S. (1904). Principles of general aesthetics. Leipzig: Barth.

-

Witasek, S. (1908). Basic lines of psychology. Leipzig: Dürr.

-

Witasek, S. (1910). Psychology of spatial perception of the eye. Heidelberg: Winter.